I performed on two liberal college campuses. This was my experience.

“My advice to you is to start drinking heavily.”

“We wanted to laugh at your jokes, Rajiv, but they just weren’t funny.” — My Mom

The first time I ever did standup, I killed.

The second time I ever did standup, I bombed. And that’s when my Mom dropped that ingenious line above on me.

That tie, though. Maybe they were just laughing at me.

Last week, I was booked to do an hour each at Amherst College and Brown University — two coastal, élite, private, liberal colleges, the type featured in stories like Nimesh Patel’s gig at Columbia University or Konstantin Kisin’s at London’s School of African and Oriental Studies. (I don’t think London is on the coast but forgive me: I went to public school.)

Comedian fashion has come a long way.

I was in New York City when several friends sent me the article about Nimesh. I texted him…

“Yo. I’m in NY. Just read about Columbia. I’ve been joking all week that I’m terrified to perform at Amherst and Brown this week. Would love to hear about your experience but understand if you’re getting bombarded and not up for discussing.👍🏾”

Much to my surprise, he immediately called me. A call? In 2018? When your phone rings unexpectedly these days, it’s almost like it sneezed. We had a 17-minute conversation about his experience, which was pretty much what you read about in PJ Media or in his own solid op-ed in The New York Times. (Boy, did I feel like a New Yorker all week, citing “a piece I just read in the Times.”) Nimesh and I were on the same show at Carolines on Broadway several years ago and he’s one of the few comics who did very well; I’m a fan generally of his standup and specifically of the joke that got him the hook.

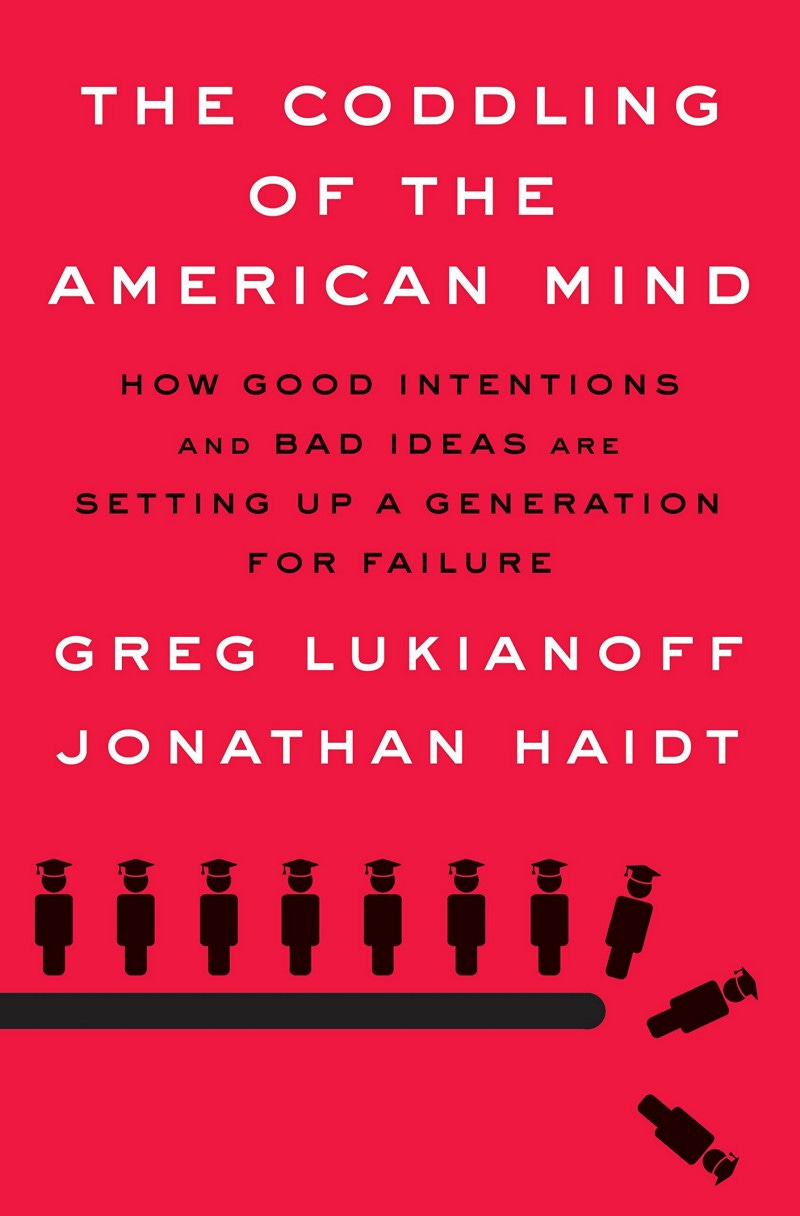

I found what happened to him and to Konstantin disturbing but not surprising. I just finished The Coddling of the American Mind by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Louganis. (It’s Greg Lukianoff but I like allusions to swimmers of the 1980s. Plus, the book was a… deep dive into the phenomenon of the hyper-PC culture prevalent on college campuses.)

Black and White and Re(a)d All Over.

One of the main action items the authors of that book suggest performers and speakers do is insist on removing phrases that refer to words as violence.

“Words, like violence,” wrote Depeche Mode (in the ’80s), on their album, Violator, implying that words are like violence but not actually violence. Words aren’t violent. They can hurt; they can wound. Verbal abuse is a thing, No Doubt. (Great ’90s band.) But they are different from actual violence, which is physical and indisputable. Whether I actually touched you is not debatable; it’s binary. I either laid a hand on you or I didn’t. And even in this case, intent matters. If I genuinely brush into you because the subway lurched (something that happened multiple times that week in New York), that legally cannot count as battery.

(A oft-neglected point is the difference between assault and battery. If I get up in your face and threaten you, that’s assault. If I actually touch you with intent to harm, that’s battery.)

So, when I encountered this in the contract…

“The College expects all members of the College community and guests to respect the dignity, freedom, and rights of others. Violence in word or deed against another; incitement or provocations to violence; conduct that exploits or coerces another; theft or the destruction of another’s property; prevention of another’s free expression of ideas by intimidation, abuse, or physical force; defamation; violation of another’s privacy; unauthorized entry and, specifically, uninvited presence in another’s room or office constitutes a material breach of this agreement.”

… even though “prevention of another’s free expression of ideas by intimidation” should’ve covered me, I struck “in word” and wrote this to the Office of Student Life advisor…

“‘Violence in word’ is a broad and legally ambiguous phrase. I’d prefer this be struck. Of course, my act is clean and respectful, but this is very open to interpretation.”

… which he accepted with a, “Everything noted is agreeable and noted.”

Because he’s a normal human being.

Still, to be sure, I asked for a phone call with him and the student organizer. I tensed up a bit when I heard him say, “Most of our students are from intersectional identities.” Oh, boy. (Oh, girl? Oh, woman? Oh, femme? Oh, non-binary?) Fortunately, they said they’d seen my stuff and I should be fine.

I ended up doing 70 minutes. Jokes about Hindus, Muslims, black people, white people, conservative positions, liberal positions, the LGBTQ community… if you’ve seen my act, you know what I mean. (Only two jokes didn’t work.) The students were fantastic; I loved every minute of being on the campus of Amherst.

Standup is cruel. In a way, my first two gigs ever were representative of how this game can be. Just as soon as you think you’ve got it cracked, you fall on your face. At the very least, it has its ups and downs. Years ago, Comedian Isaac Witty had written on his head shot hung up at Jokers Comedy Club in Ohio: “Thursday: Letterman. Friday: Dayton.” Wow, did that ever sum it up.

Determined not to follow up a Kill with a Bomb, I took the next gig just as seriously. What we often forget about any traits we may possess is that they’re not constant. There’s fluidity depending upon how we’re perceived. There are myriad quotes about stuff like this, but we all seem to have a hard time remembering this when it applies to us:

Sometimes, you’re nice. Sometimes, you’re a dick. (“A heart is not judged by how much you love but by how much you are loved by others.”)

Some days, you look good. Some days, you don’t. (“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”)

Some nights, you’re funny. Some nights, you’re not. (“Sometimes you feel like a nut; sometimes you don’t.”)

If people laugh at your jokes, you’re funny. If they don’t, you’re not. So, with that in mind, I did 75 minutes, followed by a Q&A. Two questions of note. The first one got laughter during both the Question and the Answer, probably because it was asked by a budding student standup comic. I marked the Laughs, but you can imagine them replaced with Groans on Thursday.

First Question:

Q: Did you hold back tonight? And if so, could you tell that joke now?

A: Oh, gosh. Dude, I just made it through the gig with no issues. Watch me blow it here on the dismount. OK, here goes. There were only two jokes that didn’t work last night:

“Do we have any nursing majors tonight? No Filipinos? [Laugh.] Or Malayalees? [Laugh.] I’m assuming no Registered Nurses then. You realize the only two people registered in society are Nurses and Sex Offenders? [Laugh.] What’s going on there? Is that the same registry? [Laugh.]”

OK, so that’s one. The other one, to me, is the best joke of the whole set, but it’s a thinker, and sometimes when people don’t get something right away, they’re sort of mad and then don’t really want to laugh later. OK, here goes:

“I miss Barack Obama. I miss his phrase: ‘Let me be clear.’ ‘Let me be clear.’ ‘Let me be clear.’ After nine years, I finally figured out what he meant. In racial America, he’s just tired of being a color. [Long Pause… Laugh.] ‘Dear Lord, I don’t want to be black. I don’t want to be white. Let me be clear.’” [Laugh.]

Dear Lord, Let Me Be Clear.

Second Question:

Q: What do you think of what’s happening on college campuses?

A: People need to stop being offended on others’ behalf. Let them fight their own fight. Otherwise, you’re implying they have no agency, which ironically is very condescending. Beyond that, attacking the jokes themselves is dangerous. There’s something called the Allport Scale, which measures bigotry in a society and goes from one to six. Level One is jokes. Level Six is all-out genocide. Jokes are signposts that tell you where the problems in a country are. If you rip out all of the signposts, then the problems still exist and now you have no idea where to find them. Don’t attack the joke makers — attack the issues themselves.

In conclusion, had nobody told me college campuses were overly sensitive, I never would’ve known better (or worse). For years, people ask me how I change up my act depending upon the audience. I don’t. Sure, I may throw in a few more gestures and change the way my head nods in a primarily South Asian crowd. But the content — the essence… the soul — of the act is the same. That’s why a routine is called a routine. My set was the same at The Stardome Comedy Club in Pelham, Alabama, as it was at “Brava! for Women in The Arts” in San Francisco, California.

Just be who you are. We’re all craving… I won’t use the word “authenticity” because I think it’s a phony marketing word. But I’ll say we’re all craving REALNESS. Just be real. Sure, you may run into road bumps; there are exceptions to every rule. (Who knows? I could go down in flames at my next college gig. Knock on wood.)

But more than most demographic groups, Millennials (b. 1981–1994) and iGen (b. 1995 — Present) love it when you just be yourself. Show up, do yo’ thang, and they’ll love you. Even in 2018, there’s more that unites us than divides us. People are people.

“People are people so what should it be? You and I should get along so happily.” — Depeche Mode (1984)

I think a lot of comics need a mother like mine. If you didn’t do so hot, maybe your jokes just weren’t funny?

Rajiv Satyal is a standup comic. He resides in Los Angeles.